The History of Lager in the Pacific Northwest

The history of lager in the Pacific Northwest has been a relatively steady endeavor, in contrast to the rest of America, since it’s early days in the mid-1800’s.

Yet it has especially grown and flourished over the past five years as the beer drinking public has matured, the excesses of covid have abated, capacity for larger batches has increased, and segmentation in the industry has freed craft brewers to pursue these crushable, lower calorie creations they’d prefer to drink themselves.

The latest to arrive in Oregon, actually landing this week via Day One Distribution, is Seattle-based Douglas Lagered Beer. The premise of this brewery, founded in 2023, is to reimagine the local nature of lager brands once based in the region and still popular in the Pacific Northwest, though are no longer brewed in the area nor imbued with local ingredients.

The owners and founders of Douglas are Chris Smith and John Marti, once proprietors of Seattle’s Lowercase Brewing which only recently closed. What sets their lager apart from it’s industrial predecessors and contemporaneous counterparts is three fold: it’s a Premium Lager being that it’s an over 60% grain recipe (as opposed to a Light or adjunct Lager), they source all of their raw ingredients from local suppliers (Linc Malt from Spokane Valley, the Lórien varietal from Indie Hops in Oregon, and Pilgrimage Yeast – an Andechs strain from Imperial Yeast, also in Oregon), and they brew at a larger scale without back watering (aka post-fermentation dilution). The result is a crispy, yet flavorfully balanced Lager that exhibits the drinkability and traits of a light Helles and a modern craft Pilsner.

It truly feels like a moment where the beer industry is coming full circle, focusing more on grain quality, accessibility, drinkability, lower calories, and a reasonable price point versus what’s transpired over the last 4 decades.

So how did we get here?

Foundations of American Lager & Lite Lager

During the pre-prohibition era, from the 1880’s through 1920, lager breweries in American were more akin to the locally-focused breweries in Germany and how they are today – every town seemed to have one.

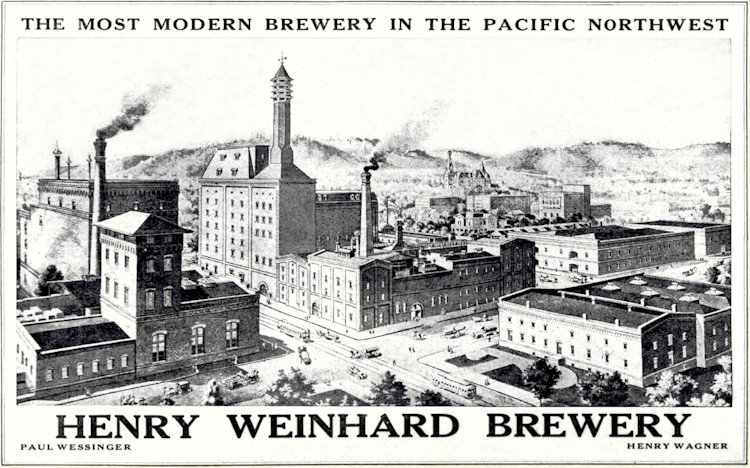

The early days of brewing in Oregon saw it’s first breweries open as early as 1852 (the contested claim of Liberty Brewing’s Henry Saxer) with the first historically verifiable brewery being Charles Barrett’s Portland Brewery and General Grocery Establishment, founded in 1854. The most renowned of the earliest brewers was of that of Henry Weinhard who bought Saxer’s Liberty in 1862, originally named City Brewery, which would go on to brew in excess of 100,000 barrels annually, exporting a vast amount of it to East Asia.

Around the same time, the Puget Sound region saw the opening of it’s first commercial brewery in 1854 by Antonio B. Rabbeson called the Washington Brewery, later renamed Seattle Brewery. The other two formidable breweries who came to define beer in the state were Rainier Brewing in Seattle around 1883 and Olympia Brewing in Tumwater in 1896.

As with most regions of the United States, Prohibition shuttered many of the PNW breweries, so those that did survive either operated with a small regional footprint or were bought outright by one of the many mid-west operations that were growing to a national scale by utilizing railroads, refrigeration, industrial production techniques, and vertical integration to minimize cost.

These larger breweries, such as Anheuser-Busch Brewing, Joseph Schlitz Brewing , Miller Brewing, Pabst Brewing, and Coors Brewing won new drinkers, before & after prohibition, by utilizing the aforementioned methods plus promotional advertising, low prices, and their German heritage story.

Almost all early American Lagers are today regarded as Premium Lager. This style is defined by the Beer Judging Certification Program as tending to have “fewer adjuncts than standard/lite lagers, and can be all-malt. Strong flavors are a fault, but premium lagers have more flavor than standard/lite lagers.”

In the 1940’s Coors became one of the earliest breweries to create what we now know as a Light or Lite Lager, where the grain bill utilizes at least 40% corn or rice as adjuncts, thus offering a lower cost, as well as less gluten and a lower calorie option.

In time, essentially from WWII until the 2000’s, all of the smaller regional Lager breweries were either absorbed by the large national brewers (AB, MillerCoors, Molson Coors, Pabst, Labatt, etc.). As a result, those favorite local lagers were now brewed at a bigger regional facility (often featuring many ownership changes) and no longer featured the locally sourced ingredients we have in abundance here, with less attention to detail, and a lower cost.

In 1966, the Rheingold Brewery introduced what’s consider the first American “Lite Beer,” Gablinger’s Extra Light Beer. While this first attempt failed in the market, a year later the recipe was adopted by Meister Brau as Meister Brau Lite which found an audience. Five years later, weighed down by debt and on the verge of closing, Meister Brau was acquired by Miller Brewing company in 1972.

After years of various breweries failed attempts at a “diet beer,” Miller ultimately released their own version of the style called Miller Lite in 1975. This version found great success, turned the American brewing world on it’s head, sparking what’s referred to as the “Lite Beer Wars” which lasted through the 90’s.

This approach effectively saturated the market with colorless, adjunct laden industrial creations that were made more for corporate success than customer satisfaction. While Lite Lager didn’t completely spell the end of the more traditional or Premium approach to Lager, it did incentivize homebrewers to create their own recipes at home, thus putting in motion a new approach to American beer, a return to handcrafted ales via the microbrewery concept or craft beer.

Craft Brewers Ascend

With a lack of options beyond industrial adjunct lagers, homebrewers in the 70’s learned and shared the process of how to brew more flavorful ales. Part of that intrigue was spurred by the growing expenses of the stagflation nature of higher prices in the late 70’s.

What originally set American craft beer apart from what came before was their full flavored and higher ABV offerings ales, not the lighter industrial lagers of yesteryear. Complex, rich, and available locally, the early days felt like a secret club of folks in the know about how good beer can actually taste.

With that success, including an expansion of formats (22oz bottles, growlers, 750 bottles, 16oz cans), craft beer differentiated itself by being perceived and marketed as a high end product, especially in comparison to the established national industrial lager complex.

Since then we’ve been through the IBU wars, a battle of barrel aged sours, the haze craze, and even a quick blip of success for smoothie sours during covid. All this differentiation within the craft sector of beer provided us with never-before-seen options and flavors.

Today, following what appears to be the exhaustion of both brewers and drinkers alike, breweries have returned to the roots of beer, opting instead to create low ABV Lagers and Ales that appeal to their steady cadre of supporters.

That exhaustion, in my estimation, came from a constant need to adhere to trends of the moment, most of which incur a higher cost of production including time & space required for barrel aging, volatile hop prices, fruit purees, expensive adjuncts (vanilla, coffee, cacao, etc.), and over the top additions such as lactose and marshmallow fluff.

While barrel aged ales (stouts, saisons, barleywine, etc.), Hazy IPA/Imperial IPAs, and fruited sours are still popular and in demand across the country, demand has declined, save the breweries who brew them best. In fact, many who’ve risen to prominence behind these styles have diversified their portfolio to now brew styles they never brewed before such as IPA and Lager, often for the sake of keeping the lights on and offer more than just a handful of esoteric styles.

It all seems a counterbalance to the escapist excess many experienced during covid – now coming back to earth from a spendthrift reality before the onset of higher inflationary pricing and more expected price increases with impact of tariffs looming on the horizon.

Further, the most recent entrants into the world of legal drinking often prefer other beverage options including non-alcoholic beverages, fermented malt beverages (FMBs) such as seltzers and ready-to-drink “cocktails” (RTDs), or opting instead for the wealth of cannabis products available legally in most states.

PNW Crafted Lagers

All of the above has bred a higher demand for lower ABV and lower calorie beer options. To retain their place in the market, brew what they prefer to drink, and actually capitalize on renewed demand for session-ability, Pacific Northwest brewers are leaning into craft lager like never before.

To be sure, there are a handful of traditional Lager focused craft breweries in the Pacific Northwest, most notably Chuckanut, Heater Allen/Gold Dot, Occidental, Wayfinder, and Zoiglhaus, yet they are still craft brands brewing at a relatively small volume, with distinctly smaller batches than the volume required to make larger, year-round batches of inexpensive lager.

This is intrinsically what makes Douglas Lager an exciting development for the PNW as it’s an inexpensive premium lager, brewed at a larger scale that isn’t owned by a huge conglomerate or brewed in Los Angeles or a huge regional production brewery at 1000bbls per batch. It’s crafted by native Washingtonians who successfully brewed just about every lager style possible over the course of Lowercase Brewing’s 11 years of existence.

So be sure to check them out in 16oz cans and on draft starting later this week, plus you can also expect their 12oz bottles to arrive as special drops from time to time. In the interim, check out a little more recent history of regionally brewed value lagers, let me know if I missed anything below, and thanks for reading!

Current and former “value craft” lager brands in the Pacific Northwest:

2016: Premium PNW Lager, Tukwila WA

2018: Seattle-Lite Lager, Seattle-Lite Brewing, Seattle, WA

2019: Freedom Lager, Culmination Brewing & Modern Times PDX, Portland, OR

2021: Heidelberg, 7 Seas Brewing, Tacoma, WA

2022: Yovu Golden Lager, Yovu Beer, Oregon City, OR

2023: Prinz Crispy/Kirkland Signature, Munich-style Helles, Deschutes Brewery, Bend, OR (Costco white-label)

2023: Douglas Lager, Seattle, WA

2024: Freight Lager, Freight Supply Co (Buoy Beer), Astoria, OR

2024: Stokes (Light, Clásica, Super Dry) Boss Rambler Beer Club, Bend, OR

2025: Multnomah Falls Lodge Centennial Premium Lager, Thunder Island, Cascade Locks, OR

RIP Seattle-Lite. They were ahead of their time. Cool place.

Heidelberg far surpassed my expectations and I find it superior to many other value lagers.

I can’t wait to try Douglas. Lowercase was outstanding. Prost!

LikeLike